Have you noticed the different sizes and colors of headings in a textbook? Have you noticed that many textbooks use text of various sizes and colors in the table of contents? Have you noticed that the table of contents usually looks like an outline? Writing is a hierarchy—and all the different colors and sizes of text tell the readers what LEVEL of the hierarchy they are on.

Levels are a key concept in creating, understanding, and analyzing outlines. In fact, formal academic outlines use the term levels: e.g., a one-level outline, two-level outline, three-level outline, etc. Put simply, an outline is a visual representation of the levels that exist inside an organized piece of writing. As such, a hidden outline exists within every piece of writing; therefore, the levels also exist. However, the outline levels differ from the writing levels in a few ways.

What follows deals primarily with levels in writing. However, understanding the levels in writing opens the door to understanding the levels in outlines. In short, you will learn both.

The Four Levels or Units of Discourse

- Level 1: Whole Composition

- Level 2: Paragraph

- Level 3: Chunk

- Level 4: Sentence

The Four Levels of Discourse model is also called the Four Units of Discourse. Both terms deal with the same material. Just as we can view light as both a particle and a wave (wave-particle duality), we can also view units of discourse as levels of discourse and vice-versa.

When we teach writing or analyze literature, viewing pieces of writing as a hierarchy of ideas is helpful. In fact, it is the main reason why outlines are such an important tool. However, students also need to understand that when we construct a piece of writing, we take a collection of lower-level parts (units) and put them together to create a whole. Each sentence is a building block for a paragraph, and each paragraph’s mission is to fit together with other paragraphs to form a whole composition. Once again, both terms are important and valuable.

To gain a better understanding of these levels or units of discourse, let’s take a look at two rather old quotes about units of discourse:

The division of discourse next higher than the sentence is the Paragraph: which is a collection of sentences with unity of purpose. Like every division of discourse, a paragraph handles and exhausts a distinct topic. – English Composition and Rhetoric (1866) by Alexander Bain

Work of this kind presupposes a unit of discourse. Of these units, there are three: the sentence, the paragraph, and the essay or whole composition. – Paragraph Writing: A Rhetoric for Colleges (1909) by Fred Newton Scott and Joseph Villiers Denny

When Bain says, “next higher than the sentence,” he indicates that these units of discourse are a hierarchy. A hierarchy, by definition, has levels. Every level in a piece of writing contains all of the building blocks for the level above it. Such is the nature of writing.

The Four Levels of Discourse

- Level 1: Whole Composition

- Level 2: Paragraph

- Level 3: Chunk

- Level 4: Sentence

As you can see, I use four levels, not three. This model adds another level to the three units of discourse. This model better reflects what students see both in outlines and in paragraphs.

If you analyze a long paragraph (8-12 sentences), you will see that the paragraph is composed of two or more groups of related sentences. If you are to outline that long paragraph, you will find chunks of connected sentences. Would you agree that students need to be able to see how ideas connect within a paragraph? I hope so! The concept of chunks opens the door for that conversation.

Now, let’s take a look at the Four Levels of Discourse.

Level 1: Whole Compositions

Students are required to become proficient in Six Main Types of Whole Compositions: 1) essays, 2) reports, 3) research papers, 4) stories, 5) letters, and 6) articles. Each whole composition will be PRIMARILY one of these Four Modes of Discourse: 1) expository, 2) narrative, 3) descriptive, or 4) argument.

One composition theorist (I forget who) argued that there is no larger unit of discourse than the whole composition. He argued that books are a connected series of whole compositions. I agree. Standard advice and common sense tell writers that the first step in writing a book is to create a basic list of necessary chapters—i.e., a list of essential whole compositions.

I used to tell students that if you can write a paragraph, you can write a book. I don’t tell them that anymore. A paragraph has only one level of beginning, middle, and ending. One level of beginning, middle, and ending has little use in the real world. Writing excellent isolated paragraphs is no guarantee that students will be able to write effective whole compositions, which have two or more levels of beginning, middle, and ending. Put simply, a series of whole compositions can be arranged into an acceptable book, while a series of paragraphs cannot.

Be sure to check out Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay on the homepage! The program is the hierarchy of ideas in a complete system and methodology that students easily understand, internalize, and apply. Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay teaches how to get ideas and organize ideas quickly and easily. Stop explaining and start creating organized and natural paragraph and multi-paragraph writers today! Your students will soon be saying, “I get it! I finally get it!”

Level 2: Paragraph

In 1918, William Strunk wrote this in The Elements of Style: “Make the paragraph the unit of composition.” To be clear, Strunk wasn’t the first to say this. Basically, we plan out our whole compositions at the paragraph level. Then, we plan out the paragraphs the best we can and write our whole composition paragraph-by-paragraph, not sentence-by-sentence.

Here is what Strunk did not say. Strunk did not say to make the paragraph the unit of instruction. Many teachers who teach the paragraph believe in the “One Good Paragraph” fallacy. They think that if their students can write one good paragraph, they can write a book. They believe the paragraph is the building block of books. It’s not! Every paragraph must fit in with and support the purpose of the whole composition just like every sentence in a paragraph must support the main point of the paragraph.

What students typically learn about paragraphs is only partially true. Be sure to read these articles to discover the true nature of paragraphs. In the first one, you will learn about various studies on paragraphs, including the one presented in Richard Braddock’s 1974 journal article “The Frequency and Placement of Topic Sentences in Expository Prose.”

- The Truth About Topic Sentences, Main Ideas, and Paragraphs

- What Is a Paragraph? Really, Teachers and Students Want to Know!

- Why Doesn’t Every Paragraph Have a Topic Sentence?

- Ten Types of Paragraph Exercises: Unity, Coherence, and Emphasis

- Topic Sentence Theory, Wisdom, Advice, and Analysis for Teaching Writing

Paragraphing in the real world is part art and part style, and it is definitely genre and audience dependent. Even for expository academic paragraph writing, there is still a great debate over what is true and what is taught compared to what professional writers actually do.

To be clear, you want your students to be able to write well-structured paragraphs inside of well-structured whole compositions before you complicate the issue. You will achieve that goal FAST with Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay.

Level 3: Chunk

How can some pieces of writing average 2.5 sentences per paragraph while others average 8-12 sentences per paragraph? If you wish to understand paragraphs, you must understand what goes on inside of paragraphs—both the long and the short ones.

Here’s the short version: Short paragraphs are often CHUNKS, and long paragraphs are composed of CHUNKS. You don’t understand paragraphs if you can’t see the chunks inside of long paragraphs. If you can’t effectively write in a “Short and Lively Paragraph Style,” the same is true.

Suppose a reader-analyst wants to understand what is happening inside a paragraph. In that case, the reader-analyst must examine and analyze the chunks of connected sentences within the paragraph. How does the writer make points? Explain things? Prove things? Make confusing concepts clear? These goals are often achieved through small groups or chunks of connected sentences.

I don’t present chunk as a formal academic writing term. That being said, the word chunk has become a formal academic term, as reflected in this quote from Van Genuchten and Cheng found in Temporal Chunk Signal Reflecting Five Hierarchical Levels in Writing Sentences (2010).

Chunks have a fundamental role in information processing in the human cognitive architecture. Chunks are individual pieces of information grouped into larger units that increase our information retention (Caroll, 2004).

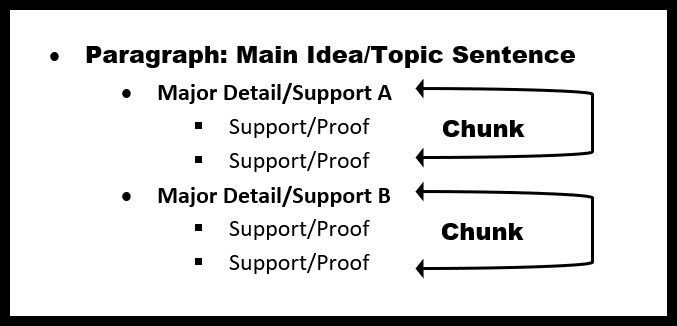

Traditionally, there are only three levels (or units) of discourse: 1) whole composition, 2) paragraph, and 3) sentence. However, the term “chunk of text” has become commonplace, and I believe there is no better term for what it represents. Without a doubt, the terms chunk and chunk of text are quite helpful when teaching writing. Furthermore, chunks are visible on outlines. Let’s look at a paragraph outline and see the chunks for ourselves:

Outlines illustrate that something exists between a paragraph and a sentence; as such, the term chunk is helpful.

If you have a long paragraph and wish to divide it, you divide it between chunks. Transitions show the movement of thought. As such, transitions are likely to identify a chunk’s beginning, middle, or ending within a paragraph. Transitions show how a chunk of sentences is connected and where the divisions exist between the chunks. You are likely to find these and other similar transitions in the beginning or middle of a chunk:

- For example, illustrating this point, reason being, first (and other enumeration terms), proving this point, likewise, similarly, in contrast, etc.

Additionally, chunks often end with these types of transitions:

- Consequently, therefore, as such, point being, put simply, in short, etc.

Please remember that we can use these transitions to begin and end paragraphs. Still, when writers place these transitions in the middle of a paragraph, they likely have something to do with a chunk of connected sentences.

As illustrated, chunks are visible on outlines. However, one must read closely and analytically to see the hidden chunks concealed within paragraphs. One must examine how the ideas expressed within sentences are connected. Here are a few (of many) ways in which sentences in a chunk may be connected:

- Statement and support; statement and explanation; point and proof; point, proof, and commentary, statement and clarification; statement and description; question and answer, etc.

A chunk is simply a small, connected group of sentences. Take a look at this simple example:

- Chunk: I bought a car. It’s red. It’s fast. Vs.

- Sentence: I bought a fast red car.

As you can see, there may be little difference between a chunk of sentences and a single sentence. In other words, when we combine sentences, we are likely combining chunks of connected sentences. When we uncombine sentences, we are likely creating chunks of sentences.

Please note that I don’t overuse the word chunk. I also use terms like “group of related sentences” and “logical breaks”—and other terms. If you wish to teach or understand the logic of how sentences and ideas relate to each other, be sure to read Academic Vocabulary for Critical Thinking, Logical Arguments, and Effective Communication. It will transform the way you think and communicate! I guarantee it!

Level 4: Sentence

In The Oxford Essential Guide to Writing (2000), Thomas S. Kane says, “It’s probably impossible to define a sentence to everyone’s satisfaction.” Jean Sherwood Rankin couldn’t agree more. She wrote the following over 100 years ago:

Far too many of the modern grammar texts are at fault in their definitions of the sentence. I quote almost at random from a few of the recent publications:

- A group of words expressing a complete thought is a sentence.

- A sentence is the expression of a complete thought in words.

But grammar takes no heed as to whether the thought expressed in any sentence be complete or not. Grammar merely demands that the expression of the thought be complete, if the result shall be called a sentence. That is to say, every sentence must be a grammatical whole, having at least one subject with its predicate verb. – Jean Sherwood Rankin – “The Sentence and the Verb” – The Elementary School Teacher (1909)

To my mind, anyone who calls a sentence a complete thought does not care about the truth. When we combine two sentences into one sentence, do we combine two complete thoughts to form one complete thought? How does that work? In short, some people believe we can combine nearly all our thoughts into one single thought simply by using the word “and.”

Is this how thinking and thoughts work? No.

- Three Complete Thoughts? I went to the store. I didn’t buy anything. I didn’t have any money.

- One Complete Thought? I went to the store, but I didn’t buy anything because I didn’t have any money.

Over 100 years ago, Rankin addressed the truth. Why do people persist with this ridiculousness? A sentence must have completeness of thought. If you add “and” to the very end of any sentence, you no longer have completeness of thought.

I will spare you the rest of my rant. Instead, here is my definition of a sentence.

Sentence Definition:

- A sentence must be a grammatical whole.

- A sentence must have a subject and a predicate, although the subject is usually implied in a command.

- A sentence must begin with a capital letter and end with a period, question mark, or exclamation mark.

- A sentence must have completeness of thought.

Of course, this is just the beginning of sentence study. The sentence is a complete world—it’s the world of grammar. And how many people claim to understand grammar fully? I’m not sure, but William Blake may have been referring to the world of the sentence when he wrote this:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand – William Blake (1757-1827) – English Poet

The Four Levels of Discourse vs. Levels in Outlines: Is There a One-to-One Connection?

Do you remember our Four Levels of Discourse?

- Level 1: Whole Composition

- Level 2: Paragraph

- Level 3: Chunk

- Level 4: Sentence

Let’s discover how these levels relate to outlining. Addressing all the issues involved with outlines and outlining would fill at least a book chapter. In short, here are three key ways in which outlining is critical:

- We use outlining to help improve and check for reading comprehension.

- We use outlining to help students organize their own writing.

- We use outlining to help create a reading-writing connection.

To achieve all this, outlines travel in two directions:

- Outline Form → to → Written Form

- Written Form → to → Outline Form

There is usually no 1-to-1 connection, correspondence, or correlation between the Four Levels of Discourse and the Levels in Outlines. However, most student writing has a 1-to-1 correlation at the first two levels: whole composition and paragraphs. And for beginning writers, it is often wise to keep the 1-to-1 connection at all levels. However, the effect of maintaining this 1-to-1 connection is confusion over what happens with long, complex, combined sentences. How do students treat these types of sentences written by others? And are students supposed to write short, formulaic, simple sentences in their whole compositions so that their sentences match the levels in their outlines? The answer is this: After the paragraph level, outlines are supposed to focus only on ideas.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Traditionally, formal academic outlines don’t count the thesis of the whole composition as a level. I suppose it’s due to the old rule in outlining that you can’t have a 1 if you don’t have a 2. So, academic outline levels leave out the most critical level—the thesis. I always call the top level “Level 0.” In short, you must know what the point of your whole composition is and include it in your outline. That’s Level 0.

Once again, formal academic outlines use the term levels. Here is how I view things for most student writing.

- Level 0: Whole Composition: thesis, premise, focus statement, controlling idea, etc.

- Level 1: Paragraph: main idea, main point, claim, controlling idea, etc.

- Level 2: Details or Support

Keep in mind that everything with levels and outlines is relative. Even a 400-page book has a Level 0. Take a look. To outline the entire book in detail would require many levels.

- Level 0: Plot: “The Odyssey” is Homer’s epic tale of Odysseus, who faces numerous trials and adventures on his quest to return home to Ithaca and reunite with his wife after the Trojan War.

In English Composition (1891), Barrett Wendell had this to say:

- We do not deliberately plan our sentences; we write them, and then revise them.

- We do deliberately plan our paragraphs, our chapters, our books; and if we plan them properly, we do not need to revise them much, if at all.

Wendell points out that although we can plan our ideas and how we wish to order our ideas, we cannot plan out every sentence. It’s just not practical. As such, we plan out the ideas but not the sentences. Writing sentences with style, variety, and fluency occurs in the moment and then through revision. Sentences are created in the moment and then fixed after the fact.

More Levels

The numbering in levels should always be considered somewhat fluid. One can always argue for a level existing above, below, or in between. Levels in writing are supposed to help build students’ understanding of the hierarchal nature of writing. Levels in writing cannot conform to a rigid dogma. Take a look at the following. Is it complete? Is it correctly ordered? Would you do it differently? Would you add levels or remove levels?

- Level 1: Series of Books

- Level 2: Book

- Level 3: Unit

- Level 4: Whole Composition/Chapter

- Level 5: Section

- Level 6: Paragraph

- Level 7: Chunk

- Level 8: Sentence

- Level 9: Clause

- Level 10: Phrase

- Level 11: Idea

- Level 12: Word

Once again, if you teach paragraph or multi-paragraph writing, you owe it to yourself to check out Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay. You will get twice the results in half the time. Also, check out Academic Vocabulary for Critical Thinking, Logical Arguments, and Effective Communication. By reading it just once, you will change the way you think and communicate forever. I guarantee it!