Teaching writing is easy, right? Just turn the page in the textbook or workbook. If only it were that simple! Most teachers think that teaching writing is hard, and if they don’t think that, then they strongly believe that teaching writing is an art. This situation exists because how one teaches writing is as important as what one teaches about writing.

This article grew out of this article: “Grammar Instruction Does Not Improve Student Writing.” After that article, I felt it was necessary to look at what works and doesn’t work in teaching writing. Teachers naturally assume that when they are turning pages in curriculum that they are getting results. Writing is a bit more complicated.

A Teaching Writing Mindset and Best Practices in Teaching Writing

It behooves all teachers to develop a Teaching Writing Mindset that is based on research, but also grounded in reality and practicality. One reason the research on teaching writing is confusing is that teachers know they must get measurable writing results, but the research never clearly explains how YOU specifically can get measurable results with your specific students.

Still, over the years the research has made clear a variety of best practices in teaching writing. In fact, here is a fantastic and free Best Practices in Teaching Writing eBook. After you read that excellent Best Practices in Teaching Writing eBook, I think you will find that understanding the research on teaching writing only gets you so far. You still have to make it happen. After all, when the time comes, the administration is going to be looking at your results, not at the research.

The quickest way to understand how to get results in teaching writing is to begin with the end in mind.

Begin with the End in Mind: Objective Writing Results and Objective Writing Progress

Be thankful for state and district writing assessments. They let you know if your writing instruction works. These assessments show objective results. Far less understood, but equally important, is objective progress. Check out the Timed Writing System to learn how to objectively monitor your students’ writing progress.

I monitor objective writing progress using the Time Writing System, and I pay close attention to the objective writing results I see on state and district writing assessments. When you monitor results and progress objectively, you learn a great deal about what really works in teaching writing.

In one sense, it doesn’t matter what the research says about teaching writing and grammar because we have objective ways to monitor our own students’ results and progress. When I began teaching writing, I was not seeing the results I had expected to see on the state and district writing assessments. The students’ writing seemed to fall apart on these assessments. I developed the Timed Writing System and I soon had a better idea of what to expect on these assessments. This was a monumental step in the right direction. I thought so, and so did my students.

Unfortunately, most teachers don’t use objective methods to evaluate writing progress. Monitoring writing progress objectively ensures that teachers will know if their writing instruction is effective or not. Monitoring writing progress objectively is important because teachers must know what works, and the proof is in the writing. If you don’t see progress using the Timed Writing System, you are not getting results. By the way, if you teach elementary school writing or struggling middle school writers, and you want measurable writing results FAST, be sure to check out Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay on the homepage.

Now let’s look at a few components of teaching writing followed by a note on how Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay relates to all this.

1. The Writer’s Workshop Methodology, Rhetoric, and Mindset.

2. Spiraling Writing Curriculum.

3. Authentic Writing, Whole Compositions, and Daily Writing Across the Curriculum.

I hope what follows helps you to think about what works and better understand how to get measurable, objective results.

Writer’s Workshop

Let’s divide Writer Workshop into three components:

1. Writer’s Workshop Methodology – Consists of a series of steps and prescribed activities for writing time.

2. Writer’s Workshop Rhetoric – Consists of A LOT OF TALK about what writing is, what it should be, how it should be taught, and how children learn. Much of this rhetoric is personal opinion and offers little practical advice on how to improve student writing. (This does not mean that a teacher cannot learn a great deal from this rhetoric.)

3. Writer’s Workshop Mindset – Students learn to write by reading and writing, and the more authentic it is, the better.

Writer’s Workshop is a major foundation of modern writing instruction. That being said, it does not need to be swallowed whole to be useful. Personally, I reject much of the Writer’s Workshop methodology and rhetoric. I find it stifling and slow-paced. Too many words! Writer’s Workshop is a model to learn from, but teachers should feel free to adapt it as needed to match their own personality and teaching style.

We will take a closer look at Writer’s Workshop in a moment, but first let’s look at what constitutes a Teaching Writing Mindset. To be clear, Writer’s Workshop is a mindset, belief structure, and philosophy about writing and teaching writing.

A Writing and Teaching Writing Mindset, Belief Structure, and Philosophy

This really is two different mindsets, belief structures, and philosophies:

1. About Writing: What constitutes good writing? What qualities are most important in creating good writing? What qualities are simply icing on the cake? How should students write as students? How should students write as creative human beings? What role does writing play in one’s life? Why does one write? Must one write? Why? What’s the most important part of writing? What does it mean to be an author or writer? Is writing a gift or a skill? How important is writing? Really? Why?

2. About Teaching Writing: How do children learn to write? How do we know that’s how they learn to write? Are we sure that’s how they learn to write? Could there be a different way? Is there only one way to teach writing? Is there a best way to teach writing? What does not work in teaching writing? How do we know it doesn’t work? How do you improve student writing? Do we teach gifted writers to write the same way we teach struggling writers to write? Why? What are the problems in teaching writing? Are there solutions for these problems?

Now for the Big Question: In The Neglected “R”: The Need for a Writing Revolution, the National Commission on Writing says that student writing is in a state of crisis, and that we need a true WRITING REVOLUTION. Universities, business employers, and government employers are all displeased with the quality of writing that graduating high school students present. In other words, no one is happy.

Why do we have this problem? How do we solve this problem?

My guess is that most teachers don’t have strong opinions or clear answers to many of the questions posed, which is why they have read this far. They are hoping to find answers to these questions. However, if you do have some kind of answer for a great many of these questions, then you have strong writing mindset. Now, is that mindset actually correct, or should I say, will it help you get results teaching writing? Let’s explore this issue.

Mindset, belief structure, and philosophy are all synonyms. However, in teaching writing, having a clear mindset and belief structure is helpful, but a dogmatic philosophy can be stiffening. The following two extremes of Teaching Writing Philosophy limit what is possible: 1) The Writer’s Workshop Philosophy, and 2) The Red Pen Philosophy. Both philosophies are so extreme that many students won’t respond well.

Most teachers who are successful at teaching writing have developed a clear belief structure about writing and teaching writing. This belief structure is likely to be a result of study, experience, and focusing on what really works. I’m going to tell you mine.

For me, writing is a useful life tool, and a pathway to logical, powerful, and clear thinking. All this creates self-confidence, success, personal power, and interpersonal power and influence. Writing is not just writing. Writing is thinking. And ideally, we transfer everything we learn about writing and thinking to our speaking.

My Teaching Writing Mindset has four components:

1. Nobody but a reader ever became a writer.

– Richard Peck – 2001 Newberry Award Winner

2. You can only learn to be a better writer by actually writing.

– Doris Lessing – 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature Winner

3. Maximum Writing Activity for Maximum Students

4. Always be Teaching Writing – Don’t focus on writing only when it’s writing time. Keep one eye on writing when reading with students. Also, when students write in daily schoolwork across the curriculum, keep one eye on subject content (correct answers) and the other eye on writing.

That’s not a dogmatic philosophy, as I’m not attached to it. Illustrating this point, I once took over a 5th grade G.A.T.E. class for the final two months of their school year. Their teacher had been a Red Pen writing teacher, and these students had responded well to that kind of writing instruction. I quickly and effectively changed my mindset. In short, I care about getting results that both the students and I feel great about.

When you determine for yourself what writing is, what it can be, and what it should be, you will be a more effective writing teacher. Students will notice your sense of purpose and passion and will respond. They will also roll their eyes and get sleepy when they disagree with your beliefs and values, that is, when your beliefs and values don’t ring true for them personally – so be on the lookout for that.

Back to Writer’s Workshop: Does Writer’s Workshop Work?

Writer’s Workshop doesn’t work for many teachers. Personally, I use many parts of Writer’s Workshop, but there are also many more parts that I do not use. Before we look at the problems of Writer’s Workshop, I want to point out two very important strengths of Writer’s Workshop:

1. Students spend the majority of writing time actually writing. They do not spend their writing time listening to teacher talk and working on isolated skill drills.

2. Writer’s Workshop allows teachers to teach a great amount of grammar and writing skills within the context of students’ own authentic writing.

The Problem with Pure Writer’s Workshop: Too Much Risk for Struggling Students

Writer’s Workshop gurus do change their tune with changing times. For example, they have tried to enter the modern world of accountability and results, but I’m not sure it rings true. Writer’s Workshop gurus are for the most part Whole Language disciples. I’m not against whole language except that it was a complete disaster in California. Few teachers could make it work. Having said that, whole language does contain a very important truth about the true nature of language. But if teachers can’t make it work – it doesn’t work!

Pure Writer’s Workshop, like pure whole language, involves too much risk. Struggling students (which includes a majority of students in the inner-city) cannot afford that risk. These struggling students can’t afford to gamble. Writer’s Workshop is risky because there is minimal direct and explicit writing instruction. In fact, the main lesson in Writer’s Workshop is called a “mini-lesson.”

What replaces the time that teachers could devote to direct and explicit writing instruction? Answer: The Writer’s Workshop rhetoric seems to emphasize student centered discovery and discussion. That sounds nice. But take a group of adults who know little about car engines and have no interest in car engines and have them discover and discuss the aspects of a four-cylinder or straight-six car engine. It’s just not an effective use of time. These people need concrete knowledge and skills. Once they are car mechanics, they will have plenty to discuss about how to make car engines more efficient, more powerful, and run better.

I’m surely not against discovery and discussion, but we have limited time. We must make choices. I prefer direct, specific, explicit, and concrete instruction – and then holding students accountable for all those writing skills in all of their whole compositions and daily writing across the curriculum. It’s all about time and choice. Note: I do quickly discuss the writing skills students learn when reading with them across the curriculum. I want students to see all of the writing skills they learn in action when reading.

Struggling writers need more instruction than a mini-lesson provides. They need instruction that makes specific skills clear and lets them know they are required to use those specific skills in their writing. They need direct and explicit instruction. And then they need to practice what they learned in that direct and explicit instruction in authentic writing.

An important truth about Pure Writer’s Workshop is that the teachers who get great results with Writer’s Workshop would get great results no matter how they taught writing. Put simply, they just get it, and they know how to communicate that to children. Additionally, they invest a lot of time in teaching writing. It’s their passion. Many of these teachers were English majors or Literature majors in college. It helps to understand the art of writing on a professional level to teach writing this way.

In short, ineffective Writer’s Workshop is the easy way to teach writing; effective Writer’s Workshop is the hard way to teach writing.

Does Spiraling Writing Curriculum Work?

The essence of Spiraling Writing Curriculum is that you just turn the page. That’s it. You keep turning the page, you keep having the students do the exercises, and soon your students can write. If this actually worked, there would be no Writer’s Workshop, and there never would have been one.

Spiraling writing curriculum is quite similar to what researchers call isolated skill drills. Nearly all writing instruction, grammar instruction, and conventions instruction contained in workbooks and on worksheets are isolated skill drills. The research CLEARLY states that grammar instruction and isolated skill drills do not improve student writing.

Spiraling writing curriculums may contain some lessons on grammar and conventions, but they try to be a serious writing program designed to bring about objective writing success. Spiraling writing curriculums usually teach a whole mishmash of writing skills and genres. Each lesson has a beginning and ending and is then forgotten until the same or similar concept is repeated later. There is never any discussion of when and why an author applies the skills and what effect it has on a piece of writing. In short, students spend time learning information about writing and then quickly practice what they learned through a short, silly, and disconnected writing exercise. The curriculum repeats this process over and over – taking students nowhere.

To be fair, all that sounds only half-bad. Unfortunately, this is exactly what the research says doesn’t work: isolated skill drills don’t improve student writing. However, as I explain in that linked article, teachers can make isolated skill drills more effective by using specific techniques. Note: It’s probably not wise for most teachers to abandon all isolated skill drills. Teacher can make them work by connecting whatever is spiraled and isolated to authentic writing across the curriculum. But remember, no writing done on a workbook page is authentic in any way. In K-2, there may some leeway in this last statement.

Spiraling writing curriculum does create a certain amount of knowledge and a certain amount of skill with that knowledge. It just doesn’t create effective writers all by itself. Mastering writing does not constitute mastering information and mastering skills. It’s knowing when, how, and why we use specific skills in real writing and the effect these strategies have on the reader. In short, we learn what works in writing largely by prewriting, writing, revising, and publishing.

Spiraling Math: All traditional math books are spiraling curriculum – i.e., isolated skill drills. Math books layer NEW knowledge on top of what students already KNEW. With math, this methodology is all but necessary because students need specific skills in order to get the correct answer. That being said, some time spent on real-world mathematical problem solving is probably beneficial even if the benefits are not evident or quantifiable in the short run.

Writing instruction should be the flip-slide of math instruction. This means that writing instruction should focus on real writing across the curriculum – but with new skills and strategies spiraled in.

Authentic Writing

Authentic = Real. We want student writing to be as meaningful and authentic as possible. In reality, it’s very difficult to make writing assignments authentic, mainly because an authentic audience is so hard to find. An authentic audience is a reader who chooses to read a piece of writing or needs to read a piece of writing for an authentic purpose. Clearly, a teacher is not an authentic audience.

For years, educators and employers alike have been on an important quest to make the classroom and the workplace more meaningful. The reason why is simple: It creates happier, more motivated, and more productive students and employees. We all want what we do to have real meaning and purpose.

Approaching Authenticity in Writing

Once again, we want student writing to be as meaningful and authentic as possible. However, we don’t want to get lost in our quest for authenticity. I’ve seen many teachers spend lots of time on writing that has little to do with the school curriculum. I don’t know if that’s a great use of time, even if it is authentic. I’ve outlined three levels of authentic writing.

1. Most Authentic: Newspaper articles for a local or school paper, blogs, pen pals, letters to people for a transactional purpose, and more.

2. Students Perceive as Authentic: Whole compositions and all daily writing across the curriculum. This kind of writing keeps students working in the curriculum and learning important content. That’s extremely valuable in itself. Students understand that they are in school to learn this material and write about this material.

3. Not Authentic: Isolated skill drills, writing exercises, spiraling writing curriculum, and isolated paragraphs.

Note: It seems to me that it’s easier to make writing authentic when students can really write. We don’t want an authentic audience to read a piece of writing and say, “My goodness! This is terrible! What are they teaching these kids?” Remember, an authentic audience is a real audience, and as such, one can’t control or silence their opinion of a piece of writing.

Publishing makes it more authentic. How could it not? There are many great ways to publish student writing. At a bare minimum, I try to have all students read a piece of writing to someone else every single day. It adds purpose to everything they write across the curriculum.

A Little Perspective: Five Elements of Writing Instruction

Let’s take a quick look at five elements of writing instruction. To be clear, this is a very short list. However, it puts a few things we have talked about in perspective.

1. Teaching Writing Mindset and Belief Structure

2. Whole Compositions and Authentic Writing

3. Daily Writing Across the Curriculum and Authentic Writing

4. Holding Students Accountable for Writing Skills in Whole Compositions and in Daily Writing Across the Curriculum

5. Isolated Skill Drills: Spiraling Writing Curriculum, Grammar Instruction, Conventions Instruction, Workbooks, and Worksheets

1. Teaching Writing Mindset and Belief Structure

We’ve already discussed this as it relates to Writer’s Workshop. All of these topics are equally important and enlightening: Six Traits of Writing, State Writing Standards, The Writing Process, The Reading-Writing Connection, Authentic Writing, and Understanding of Genre.

2. Whole Compositions and Authentic Writing

Students perceive whole compositions (essays, reports, stories, research papers, letters, and articles) as real writing. Unfortunately, whole compositions are neglected because teachers and students struggle with them. As a result, teachers overuse isolated paragraphs. Unfortunately, isolated paragraphs have little value in the real world, and furthermore, what we teach students about paragraphs when we teach isolated paragraphs is only partially true. The real truth about paragraphs lies in how writers use them in whole compositions. For this reason, isolated paragraphs are rarely authentic. It’s only in a classroom that a person writes an isolated paragraph.

Whole compositions come close to authenticity. There is a feeling of purpose with a whole composition. And when students take pride in writing their whole compositions, they write for themselves, and that is an authentic audience and an authentic purpose. Note: I’m of the opinion that writing many short whole compositions is more effective in improving student writing than writing a few large whole compositions.

3. Daily Writing Across the Curriculum and Authentic Writing

Along with whole compositions, students perceive daily writing in the content areas as being more authentic than isolated writing assignments and exercises. Students understand that writing about what they are learning is an important part of school. They understand that they must demonstrate in writing what they have learned. What would school like be if we removed this component? I have no idea!

This kind of daily writing across the curriculum comes in many forms: short answers, constructed response, comprehension questions, reflecting on learning, learning logs, journals, note taking, and more. All of this kind of writing has a real purpose – to demonstrate knowledge and to explore the learning process. It’s not writing just to show you can write, as is the case with all isolated skill drills.

Keep in mind that teachers can always assign one grade for content and another grade (or checkmark) for writing. Students deserve full credit for correct answers in the content areas, even if the writing is lacking.

4. Holding Students Accountable for Writing Skills in Whole Compositions and in Daily Writing Across the Curriculum

Teachers must hold students accountable for applying their writing skills across the curriculum. There are many ways to achieve this: rubrics, checklists, feedback, grades, conferencing, commenting, diagnostic-reflective portfolios, responding to student writing, evaluation, holistic scoring, publishing, and the red pen.

Whole Compositions: If students are writing lots of whole compositions, holistic scoring with a Six Traits rubric is the fastest, most effective way to stay on top of student writing. Ideally, this will be just one tool in your tool belt.

Daily Writing Across the Curriculum: In order to monitor this type of writing, teachers must figure out what works in their classrooms. Systems and routines are essential. It may be best to create two categories: 1) core writing skills, and 2) advanced writing skills. Additionally, or perhaps, teachers may target different skills with different (small) checklists at different times. You can also grade this type of writing using a quick and gentle approach e.g., checkmark minus, checkmark, checkmark plus. Try not to confuse writing skills with content knowledge. Grade them separately.

5. Isolated Skill Drills: Spiraling Writing Curriculum, Grammar Instruction, Conventions Instruction, Workbooks, and Worksheets

Even though the research says grammar instruction and isolated skill drills (including spiraling writing curriculum) are not effective in improving student writing, most teachers should not abandon them completely. They should just use them quickly and with the understanding that the real benefit comes from holding students accountable for applying those skills in whole compositions and authentic writing across the curriculum. Be sure to read the linked article to find out how to get better results with grammar instruction and isolated skill drills.

Writing is a Skill: A Final Word on Spiraling Writing Curriculum and Isolated Skill Drills

Writing is a skill, and learning information does not create a skill. Learning information creates knowledge; it is the application of knowledge that creates skill. Clearly, effective writing requires the development and application of many skills, not just one. The Six Traits of Writing groups these skills into six categories. Let’s look at these skills a different way and group them into three categories. The first two are self-explanatory.

1. The skill of applying writing techniques, writing strategies, and writing knowledge.

2. The skill of clear, logical thinking.

3. The skill of Rewriting (editing, revising, proofreading). – Revising is where everything one learns about writing comes together. Furthermore, I think this is where students truly internalize a high percentage of writing skills. Rewriting involves a prolonged thinking, rethinking, and application of everything one knows about writing. Rewriting deserves its own category for this reason alone. However, it deserves its own category for another reason.

The second reason Rewriting gets its own category is that it’s difficult to get rid of the bias that makes us believe we wrote things correctly the first time. It’s difficult to correctly and objectively see what we put on the page, let alone to rethink what we put on the page. It’s difficult to think about and consider all the possible things that could be wrong in a piece of writing and all the ways we could make it better. Rewriting skills can be taught and should be taught, but they only become a natural part of a student’s thinking process by rewriting real writing – lots of real writing.

Note: As important as Rewriting is, I don’t overemphasize Rewriting with elementary school students and struggling middle school writers. I try to leave them wanting more time to make their writing perfect. After all, they will soon have another chance to write, and they will try even harder to get it right the first time. There is only so much time. However, if I taught advanced middle school writers or high school students, I might overemphasize Rewriting.

Each of these three categories of skills requires making choices and using good judgment. These skills must also become a part of muscle memory – both mental and physical. In other words, effective writers develop a bag of tricks and a style of writing that they use repeatedly. In one sense, a person’s writing is like a person’s fingerprint.

So, can you see why students cannot master these writing skills through silly, disconnected, spiraling writing exercises? Once again:

You can only learn to be a better writer by actually writing.

– Doris Lessing – 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature Winner

Teachers hope that spiraling writing curriculum, grammar instruction, conventions instruction, workbooks, and worksheets create effective writers. Teaching writing would be easy if they did!

Why Spiraling Writing Curriculum and Isolated Skill Drills Don’t Work: A to B; A to B; A to B; A to B; A to B.

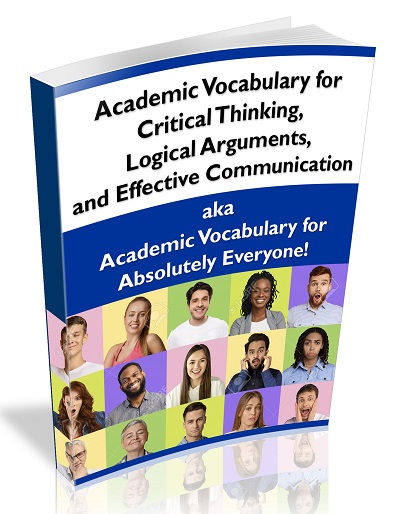

The problem with grammar instruction and spiraling writing curriculum is that the lessons only take students from point A to point B.

The Points on the Road to Student Writing Success:

• A = The beginning of a writing or grammar lesson.

• B = The end of a writing or grammar lesson; the lesson’s objective has been achieved.

• C = Students are independent and competent student writers. They write effectively at grade level or higher across the curriculum in all the required types of writing.

• D = Students write high-quality university-level academic essays and research papers. The writing is so effective that prospective employers are impressed and feel the writing will successfully represent their company.

Points C and D are Big Picture goals. Point B is a small picture goal. Most grammar and writing instruction continually and repeatedly takes students from point A to point B. This kind of instruction focuses on the small picture and hopes it adds up to big picture goals.

Most writing teachers understand this aspect of point A to point B lessons and try dearly to connect it all together. As teachers, we know it is our job to take students from point A to point C, and eventually to point D.

The reality of teaching writing is this: teachers are the ones who must connect all these point A to point B lessons and reach point C and then point D. It’s much easier to accomplish this when a great deal of focus is devoted to writing whole compositions across the curriculum.

Put simply, taking student from point A to point B repeatedly takes them nowhere. Most grammar programs and spiraling writing curriculums don’t understand this.

The Missing Piece of the Puzzle – Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay

Teaching writing is a puzzle. As you can see, there are many pieces in that puzzle. Unfortunately, when it’s time for a state or district writing assessment, people only want to know if the teacher pulled it all together for the students and delivered writing success.

Recently, one teacher said this: “Finding Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay was like finding the one piece of the puzzle that makes all these other materials work. I just wish I had found your program first.”

Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay is both a foundation and a framework. After students have internalized the program, it’s easy for teachers to spiral in advanced writing skills and grammar instruction while keeping the focus on students’ own authentic writing. This is what the research says works!

There is no lack of writing and grammar lessons in the world. What has been lacking is an effective way to create a writing foundation:

• A foundation that can be built upon.

• A foundation that teachers and students understand and enjoy working with.

• A foundation that more advanced lessons can be layered on top of and connected to.

• A foundation that makes everything involved in writing connected.

Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay does all this! If you are an elementary school teacher, it’s quick and easy to build that writing foundation. If you teach struggling middle school writers, you will save yourself and your students endless hours of grief and frustration!