Why is the term Unity Statements ™ so valuable in teaching writing? Well, students will not understand topic sentences, thesis statements, or even organization in writing until they understand Unity Statements ™. To understand Unity Statements ™, students need to understand Unity, so be sure to read these two posts:

- Unity in Writing: Teach Students to Hammer Their Thoughts into Unity

- How to Teach Unity in Writing While Teaching the Writing Process and Improve Your Students’ Writing

This third post on unity tackles a different aspect of unity. It addresses all the ways unity exists or is created in a piece of writing. To understand the concept of unity and its importance in reading and writing, be sure to read the other posts.

Why Do Reading and Writing Teachers Need to Develop a Deep Understanding of Unity?

1. Teaching Writing: Unity helps students create focused, organized, coherent pieces of writing where every idea supports the main message.

2. Teaching Reading: Understanding unity helps students to comprehend texts better, as they can identify how different parts contribute to the overall theme, argument, structure, text, etc. Furthermore, understanding unity helps students identify both clearly stated and implied main points, etc. Unity helps readers grasp both the parts and the whole and how the parts contribute to and create the whole.

Unity of Purpose: The practical application of unity is unity of purpose. Legendary basketball coach Phil Jackson describes unity of purpose as the key ingredient for winning championships. In 1866, Alexander Bain, the creator of modern paragraph theory, defined a paragraph this way: A paragraph is a collection of sentences with unity of purpose.

Unity in writing really means unity of purpose. The parts all contribute to creating a unified whole. This article will focus on unity of purpose in the message or content. However, unity of purpose also applies to many different aspects of writing. Take a look!

Various Aspects of Unity of Purpose: Unity of purpose in message, point of view, structure, voice, style, tone, voice, theme, mood, plot, and character development.

You May Also Be Interested In:

1. Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay: The fastest, most effective way to teach clear and organized multi-paragraph writing… Guaranteed!

2. Academic Vocabulary for Critical Thinking, Logical Arguments, and Effective Communication, aka Academic Vocabulary for Absolutely Everyone! Improve the way you think and communicate quickly, easily, and forever!

Unity vs. Lack of Unity

Unity in a text does not automatically exist. Unity in writing is something we create. Irish poet William Butler Yeats (1865–1939) put it best when he said, “Hammer your thoughts into unity.”

As readers and writers, we must grasp the extent to which unity exists. As writers, we must “hammer our thoughts into unity.” As readers, we are often required to identify, summarize, or state the unity. In short, what’s the point? As critics, we must identify the unity problems.

One time-tested technique for fixing problematic writing is to create an outline after the fact. We create an outline to see what actually exists. Did we say what we think we said or wanted to say? An outline will reveal the truth.

Moving forward, we will assume that unity does exist.

Why Don’t Teachers Use the Term Unity More in Writing Instruction?

Here’s a scene I’ve seen played out in a few movies: An editor takes a red pen and crosses out entire paragraphs, sections, and even entire pages and says, “Okay, get it ready. It goes in the next issue.” This editor can see through the clutter to get to the central message and removes everything unnecessary to communicate that message.

Teachers often don’t talk about unity at all. Regardless, poor unity causes many problems. Crossing out, removing, or deleting text is usually a clear sign of attempting to solve a unity problem. To be clear, ideas can be related and still harm unity. On some level, everything is related.

Just because we don’t always use the term unity, does not mean unity is not crucial. Here are some terms related to poor unity. Do any of these terms ring a bell when thinking about student writing?

Terms Related to Poor Unity: Disjointed, off-topic, unnecessary, it doesn’t belong, takes us off track, distracting, inconsistent, choppy, unclear, uneven, muddled, chaotic, confusing, rambling, pointless, a mess, a disaster, too long, too boring, meandering.

Please note that I rarely, if ever, say things like, “There is a problem with your paragraph’s or whole composition’s unity.” That sounds weird. Having said that, I do teach unity in a way where students grasp that creating something that feels like a unified whole is critical. Once again, we can address the unity concept with one critical question: What’s your point? What’s your point in each paragraph? What’s your point in your whole composition?

Teachers frequently discuss how the parts all contribute to the whole, and the whole is composed of parts. However, teachers fail to mention that the parts are all unified wholes, and they contribute to form a larger unified whole. This tells students that we include what is essential and leave out what is not.

I invented the terms Unity Statements ™ and Unity Structures ™ because so many terms exist related to unity, but none address the concept of Unity. I felt it was essential to bring Unity to the forefront and teach students what all those diverse unity terms are really getting at.

Unity: Digressions and Exceptions to Unity

In The Catcher in the Rye (1951). Holden Caulfield says, “The trouble with me is, I like it when somebody digresses. It’s more interesting and all.”

If you ever read footnotes, endnotes, or appendices and find them extremely valuable or interesting, you agree with Holden. In short, these parts of a text are digressions. Additionally, parentheticals and many boxed sidebars, etc., are also digressions.

Many textbooks are full of digressions that address important or interesting concepts. Textbooks often contain entire sections or appendices that are required by the state or district, but that feel like digressions.

The Structure of Unity of Purpose: Hierarchy of Ideas, Outlines, Tree Diagrams, and Unity Umbrellas

In case you are wondering, the Hierarchy of Ideas, Outlines, Tree Diagrams, and Unity Umbrellas all illustrate the same concept. They illustrate how ideas connect to form a unified whole. They also show the structure of unity.

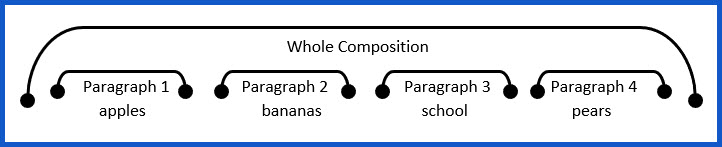

All whole compositions and all paragraphs should have unity of purpose or oneness. In other words, all whole compositions and all paragraphs should be about just one thing. Paragraphs are a whole and have their own unity. However, paragraphs are also a part of a whole composition, which means they contribute to the overall unified message of the whole composition.

A hierarchy of ideas captures this unity. By definition, the hierarchy must be a unity. Outlines illustrate this hierarchy of ideas. This is why outlines are an essential and common instructional tool for reading and writing instruction. Once again, a hierarchy of ideas illustrates how ideas connect to form a unified whole. That’s also what an outline does.

The concept of the umbrella is also helpful. In short, each paragraph and whole composition sits under an Umbrella of Unity—or a Unity Umbrella. Here is how Unity Umbrellas look:

Which of these does not belong? It’s easy to see that “school” does not belong. It’s easy to see because the umbrella makes the concept of unity concrete. Once again, outlines and tree diagrams are similar.

Writers constantly try to figure out how their current thoughts fit in with their paragraphs and the whole composition. Writers constantly ask questions like these: What’s my point? What is this about? What am I trying to say? Am I on track? These questions are a search for unity. For a skilled writer, these questions are like a computer’s operating system—always running.

Unity Statements vs. Unity Structures

Moving forward, we will focus on Unity Statements. A statement is a declarative sentence. A statement is not a question, heading, or title. To be clear, statements are not incomplete sentences.

I try not to misuse terms, so I also use the term “Unity Structures.” A unity structure is anything that captures the unity of something. Table of contents do that. Frequently, summaries, conclusions, or reviews do that. Various graphics like timelines or charts may capture unity. Graphics usually capture the unity of one aspect in a way similar to what a paragraph or section does.

Furthermore, a unified color scheme would be a unity structure. Both plot and theme are unity structures. Of course, we frequently state the plot and theme in unity statements. However, as they exist in the story, they are simply structures.

Also, outlines, tree diagrams, mind maps, etc., are unity structures.

Two Forms of Unity: Stated Unity and Unstated Unity

This is a vital concept related to unity.

1. Stated Unity: Topic sentences and thesis statements state the unity. This is why I call them unity statements.

2. Unstated Unity: Stories are an exercise in unstated unity. As a rule, we don’t state the most important aspects of a story that capture this unity. That ruins the story. Show, don’t tell.

Even though main ideas or topic sentences are often implied, they still exist as unity statements. However, when implied, it’s the reader’s job to construct that main idea or topic sentence in their mind as they read. This is called reading comprehension. If we don’t comprehend the implied main ideas, we don’t comprehend the text. It’s that simple.

Unity exists in two forms: 1) Stated Unity and 2) Unstated Unity. Whether the unity is stated or unstated, all of the ideas fit under a Unity Umbrella. If an idea or paragraph does not fit under that umbrella, it’s called a digression—it’s off-topic.

By the way, the topic sentence research mentioned above was done on expository text. Narrative stories use far fewer topic sentences, and the most important points are rarely explicitly stated. One of the most essential maxims in storytelling is “show, don’t tell.” The result of this maxim is to imply, not state.

Unstated Unity: Implied Unity Statements

As I say elsewhere, unity is not implied. Unity exists to the extent it exists. However, unity statements ARE often implied. For example, topic sentences are implied at least half the time in professional writing. Read the research to understand what this means.

Worth Mentioning: Every Division in Writing Implies Unity

Every division in writing contains implied unity. Paragraphs, whole compositions, sections, chapters, units, and books all imply that the contents within are a unified whole. Even without any concrete knowledge of unity in writing, many novice writers intuitively divide based on the concept of unity.

Even some second graders can write in decent unified multi-paragraph form because they naturally grasp how something feels and sounds when it starts and ends. Writers divide when one thing ends, and another thing begins.

Of course, divisions do not always contain perfect unity. In fact, the divisions in incoherent writing usually contain poor unity.

Stated Unity: Unity Statements

Terms like topic sentence don’t capture what a paragraph is. In contrast, calling it a Unity Statement does. A topic sentence states a paragraph’s unity of purpose. Likewise, a thesis statement states a whole composition’s unity of purpose. Another way to look at it is that writers build unity around a simple question: What’s your point? That point is often stated in a Unity Statement.

A unity statement can’t state unity if unity does not exist. The unity statement will instead highlight the lack of unity.

Once again, we have various types of statements and structures that address unity. Take a look!

1. Unity Statements: Complete Sentences: Topic sentences, thesis statements, unity questions, umbrella statements, etc.

2. Unity Structures: Incomplete Sentences: Heading, titles, etc. Also, outlines capture a text’s unity at multiple levels and typically use incomplete sentences.

Readers and writers commonly state what a paragraph or whole composition is about in a single complete sentence. Furthermore, incomplete sentences (e.g., most headings and titles) often serve the same function. Here are some terms associated with these unity statements and structures:

1. Paragraphs: Topic sentences, claims, controlling idea statements, umbrella statements, and questions.

2. Sections, Units, Lessons, Chapters, etc.: Headings, titles.

3. Whole Compositions: Thesis statements, controlling idea statements, umbrella statements, titles.

More Terms: Once again, I invented the terms Unity Statements ™ and Unity Structures ™ because so many terms exist related to unity. Here are a few more of these terms.

4. Main ideas, main points, and controlling ideas are sometimes stated in concluding sentences and conclusions.

5. Unity Questions: Questions often function as strong expressions of unity, as what follows is surely an answer to that specific question. Some textbooks wisely use a question for every single heading.

Types of Unity Statements in Paragraphs

Unity Statements create a Unity Umbrella. In other words, everything else in the paragraph or whole composition can be traced back to that one sentence.

Unity Statements in Paragraphs

Everyone has heard of a topic sentence. Topic sentence may be the worst writing term ever invented because, in common usage, it’s unclear and undefined what a topic sentence does. The reality is that many different sentences in a paragraph may state the topic to some degree. After all, all of the sentences are supposed to be about the topic.

That is concrete and makes sense. If the topic sentence doesn’t state the main idea, how is it different from any other sentence in the paragraph? Once again, in a paragraph, every sentence relates to the topic. Furthermore, every sentence may mention the topic. Is a topic sentence simply the first sentence that does? A true topic sentence should state the main idea or point. However, that topic sentence ideal is not that practical.

For my own sanity, I’ve concluded that there are two basic types of topic sentences.

- States the main idea or main point.

- Doesn’t state the main idea or main point.

Here is a quick and incomplete overview. Please Note: I often use the terms “controlling idea” and “controlling idea statements.” However, I left these terms out of this discussion.

1. States the Main Idea or Main Point: e.g., Claims: A claim is a statement that requires evidence, proof, or sound reasoning to be taken seriously. An opinion you want others to take seriously and are willing to provide evidence, proof, or sound reasoning is also a claim. Claims as topic sentences always state the main idea or point. Here are two claims:

- Blue is by far the best color.

- The United States should have stayed out of the Vietnam War.

2. Doesn’t State the Main Idea or Main Point: e.g., General Statements and Door Openers: As a rule, this type of topic sentence may hint at the main idea or point but doesn’t state it. General statements are door openers. Both types may or may not capture the controlling idea of the paragraph.

Once again, the research shows that topic sentences are implied at least half the time in professional writing. However, I suspect that most paragraphs have a sentence somewhere near the beginning that is at least a General Statement or Door Opener. Although these types of sentences don’t usually state the main idea, they do introduce the topic. In other words, we can trace everything else in the paragraph back to that one sentence.

To be clear, you must examine a paragraph as a whole to distinguish between these different types of topic sentences. Does the topic sentence truly express the paragraph’s main idea, controlling idea, or does it just open the door? As a rule, it doesn’t matter. Take a look.

- The common house cat is a fascinating animal.

The main point of this paragraph is probably to inform the reader about cats. That sentence doesn’t function as a claim the writer will try to prove. This sentence does express the controlling idea. It also serves as a door opener and is a general statement. Take a look at this next sentence.

- It’s extremely hot today.

We don’t know what this sentence will do in a paragraph. This sentence could start many different types of paragraphs. Does it express the controlling idea? I don’t know. It may simply be a door opener for discussing things you can do on a hot day. Or it may go on to explain the atmospheric conditions that create this hot weather. This sentence may follow it:

- In contrast, yesterday was quite cold.

That sentence can start many different types of paragraphs. Does that sentence express the main point? Maybe. Or it may lead to something else related to that hot day or to climate change. What will follow? How hot? What happened on that hot day? How does it feel on that hot day? Implications or consequences of being hot? Why it was so hot? Hot compared to what? Hot caused by what? Thoughts or reflections about hot days? —etc.

In short, that sentence will likely function as a General Statement, Door Opener, or Controlling Idea Statement. Will it be a topic sentence? Call it what you want.

Final Note on Paragraphs and Unity: In many publications, writers use a “Short and Lively Paragraph Style.” Think newspapers, magazines, etc. In my opinion, the number one rule that exists in all paragraph writing is the rule of unity. However you divide your text, you want your paragraphs to be about just one thing. You want every paragraph to form a unified whole.

Unstated Unity and Unity Statements in Whole Compositions

Every whole composition in every formal genre must have unity. Stories, arguments, expository texts, and descriptive writing must all have unity. In other words, every paragraph and every sentence in every paragraph must somehow help to support a single Umbrella Idea or Unified Idea or Concept.

It’s worth mentioning that various types of personal, reflective, or informal writing may not require unity in the whole composition. Although these types of writing may have a high degree of unity, a unified message is not the point of these types of writing. The point of these types of writing is to explore or reflect, sometimes in many different unrelated directions. Having said that, if you wish to publish them, you will likely need to edit them to create a sense of unity. Furthermore, I encourage unified paragraph structure in all student writing as I don’t want students to practice poor paragraph structure.

Although the names of Umbrella Ideas may differ depending on the genre, for the most part, they do the same thing. Once again, unity is often stated or expressed in a single sentence, heading, title, etc. When not explicitly stated or expressed, the unity still exists. The unity is for the reader to grasp.

It would keep things simple to say that unstated unity is implied, but that’s a problematic term in this case. The unity exists to whatever extent it exists. Readers identify or interpret unity but don’t exactly infer it. It’s like how when we identify a type of rock, we don’t infer what it is. We analyze the rock and see what’s there.

We have three types of whole composition Unity Statements:

1. Thesis Statements

Thesis statements express a debatable position or idea. In short, thesis statements are claims, and by definition, claims are debatable. The rest of the whole composition, usually a persuasive or argument essay, goes on to prove the thesis statement. If the statement is not debatable, it’s not a thesis statement.

a. Thesis Statement: School uniforms violate students’ free speech rights and must be abolished.

The term “thesis statements” should have a specific meaning reserved for arguments. However, people use the term in various ways. Many great stories are constructed around an argument, so these stories are built around an unstated thesis statement.

The reality of life is that we must prove much of what we say even when it’s common knowledge. In short, people don’t believe something if they don’t understand it. Therefore, expository text is often similar to argument.

Are these thesis statements? They will likely require explanation, support, and even proof to be taken seriously.

- We must leave by 3 p.m. to make it to the dentist appointment on time.

- Black holes exist.

- Plants have five basic needs.

- Dark matter is a theoretical form of matter that comprises much of the universe.

2. General Statements or Controlling Idea Statements

Most expository and informational texts will have a sentence somewhere in the introduction that captures the unity of the whole composition. Most skilled writers will create one without even trying. They do so because it sounds and feels right. Of course, they may simply create a sense of curiosity that captures the forthcoming unity.

Although whole compositions often contain Door Openers, they likely also contain stronger Unity Statements like General Statements or Controlling Idea Statements. In reality, most whole compositions benefit from strong unity statements. This is the old “Tell Them, Tell Them, Tell Them” principle.

- Tell them what you are going to tell them.

- Tell them.

- Tell them what you told them.

To be clear, these types of unity statements don’t require that the statement expresses something debatable. Having said that, most things are debatable to some degree or for some audiences. Once again, people don’t believe what they don’t understand. By making them understand, you are persuading them that what you say is true.

- General Statement: The Space Race was an exciting and extraordinary time in human history.

- Controlling Idea Statement: Today, you will learn four ways to cook chicken.

It’s worth mentioning that next to every Door Opener, you can place an even stronger General Statement. Next to every General Statement, you can place an even stronger Controlling Idea Statement. Writing is an art! Don’t believe it has to be any one way.

Mission Statements: Unity Statements In the Real World

Unity is a vital concept in everything that requires organization. Although I don’t discuss it here, UNITY walks hand in hand with DIVISION. Division deals with parts and wholes. Everything related to organization deals with parts and wholes!

Unity is a vital concept in writing, art, and music. It’s also vital in many real-world activities, including sports and business. Once again, the unity in paragraphs and whole compositions is often stated in a single sentence. This single-sentence concept is not used only in writing. In fact, most large businesses attempt to state their company mission in a single sentence called a mission statement. That mission statement functions as an umbrella for the entire business and all its activities. It’s a unity statement!

Let’s examine eleven unity statements that capture trillions of dollars of economic value and activity.

Eleven Mission Statements that Guide Trillions of Dollars of Value and Economic Activity

You will develop a deep understanding of unity by reading these mission statements. Most of these mission statements originated many years ago, and I’m sure some have been expanded upon or changed. However, these mission statements still capture the heart of these massive corporations.

1. Facebook: “Facebook’s mission is to give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected.”

2. Google: “Google’s mission: to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

3. Twitter: “Twitter is a service for friends, family, and co-workers to communicate and stay connected through the exchange of quick, frequent answers to one simple question: What are you doing?”

4. eBay: “eBay’s mission is to provide a global trading platform where practically anyone can trade practically anything.”

5. Microsoft: “Our Mission: At Microsoft, we work to help people and businesses throughout the world realize their full potential.”

6. McDonald’s: “McDonald’s vision is to be the world’s best quick service restaurant experience. Being the best means providing outstanding quality, service, cleanliness, and value, so that we make every customer in every restaurant smile.”

7. Coca-Cola: “Our Mission: To refresh the world… To inspire moments of optimism and happiness… To create value and make a difference.”

8. Sony: “To experience the joy of advancing and applying technology for the benefit of the public.”

9. Pizza Hut: “We take pride in making a perfect pizza and providing courteous and helpful service on time, all the time. Every customer says, “I’ll be back!”

10. Target Stores: “Our mission is to make Target the preferred shopping destination for our guests by delivering outstanding value, continuous innovation and an exceptional guest experience by consistently fulfilling our Expect More. Pay Less. ® brand promise.”

11. Disney: “We create happiness by providing the finest in entertainment for people of all ages, everywhere.”

Conclusion: Teach Students to Hammer Their Thoughts Into Unity

You don’t know what to say? You can’t see what you are trying to say? Hammer your thoughts into unity!

In reality, we hammer our thoughts into unity in every stage of the writing process. Wise writers attempt to do most of the hammering in the prewriting stage. But the reality is that no matter how skilled we are at prewriting, we will continue to hammer away while writing and rewriting. Furthermore, publishing often adds a new level of clarity on our main points.

Do you teach writing? Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay is the program that teaches students how to hammer their thoughts into unity quickly and easily! It uses the A, B, C Sentence ™ and Secret A, B, C Sentence ™ to build a practical mastery of the Hierarchy of Ideas in writing! Unity is a guaranteed outcome since every idea connects through A, B, C thinking! This program is the fastest, most effective way to teach students to create clear and organized paragraph and multi-paragraph writing… Guaranteed!